We know that an apartment building can burn down because there’s not enough water pressure to fill a fire hose — because water that should have filled the fire hose instead gushed out of thousands of pipes that had cracked in the cold.

We know that in an unfettered free market guided only by the law of supply and demand, utility bills can to go through the roof when the wholesale price of natural gas spikes 10,000% because pipelines intentionally left un-winterized freeze. And we know that higher commodity prices can ripple through the economy, raising customers’ bills throughout the country.

No light. No heat. No water. No internet. No gas. No money. No help. Nowhere to go.

Food lines. Empty shelves. Burst pipes. Wrecked homes. Derailed lives.

From suburban comfort to Dickensian despair with the flip of switch.

••••••••••••

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder last summer, as Black Lives Matter protests began to ramp up, a friend explained “privilege” to me as everything you don’t have to worry about when you get up in the morning. “Of course,” I thought, “that’s exactly what it is.” For the fortunate few, the list is long. Privilege is what you get to take for granted — what you don’t realize deserves your gratitude. And now, after a harrowing week of power outages and burst pipes in Texas, we can add to the list:

- a reliable electric grid

- plumbing

- and a functioning municipal water supply

El Paso is proof to the lie of Texas’ energy policy. This bustling city of 1.5 million on the Mexican border opted out of being part of the independent Texas grid, instead joining the Western Grid, which covers the entire western United States and is subject federal regulation. That includes a requirement to winterize power plants and pipelines. While Texans in the rest of the state shivered under the covers in the dark, worried about whether their pipes would burst and where they would find enough clean water to survive, the lights stayed on in El Paso.

The mess in Texas is entirely of Texas’ making — a mess made all but inevitable by the combined machinations of oil and gas producers, power providers and a legislature packed with politicians whose purpose was to make their deregulated dreams come true. Together they created a system optimized for profit and shareholder value, pinching pennies any way they could. Absent any regulatory requirement, the cost of winterizing critical infrastructure was framed as anti-competitive, anti-business.

Everyone played by the jerry-rigged rules. Everything was legal.

It just wasn’t right.

What if?

But what if it could be put right? Texas needs to be rebuilt. Millions of burst pipes have left behind a legacy of floods, fallen ceilings, soggy walls, cracked water mains and mold — boatloads of asthma-inducing toxic mold, adding yet another layer of hardship for those already threatened by Covid. Thanks to an energy policy that failed almost everyone, millions of Texans are now at risk of developing a new, lifelong “pre-existing condition.”

Bad energy policy is also bad for business. When the power goes down, factories, offices and shops close and everything pretty much grinds to a halt. Cash registers don’t work. You can’t even charge a cell phone. A grid maintained on the cheap comes at a steep cost.

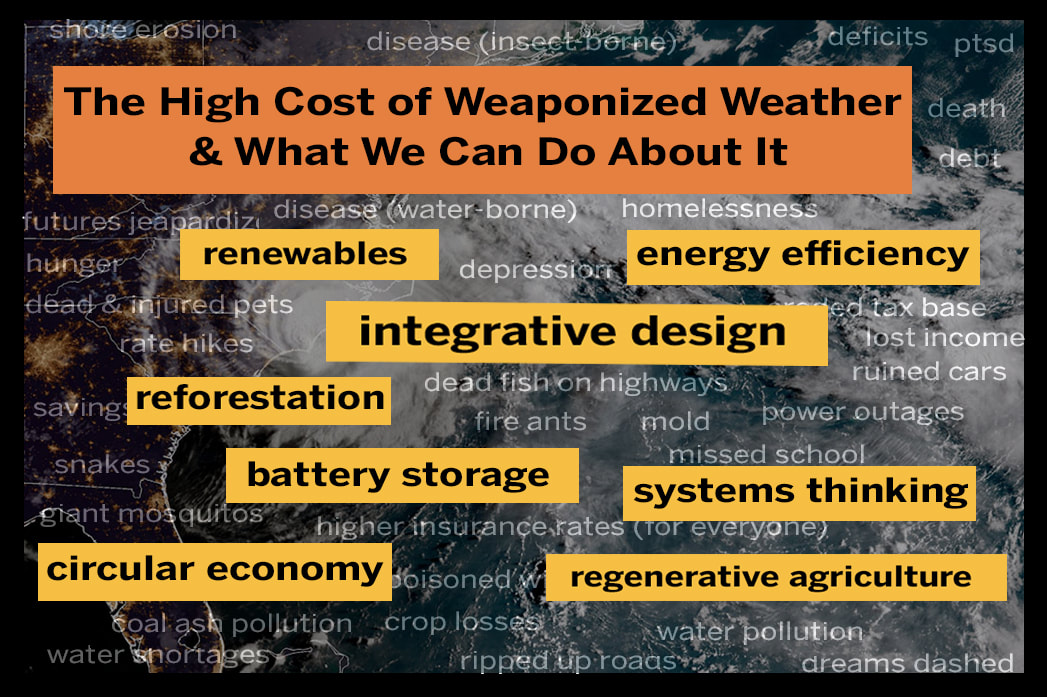

So for once, let us not simply “build back” or even “build back better,” but instead “build back different.” This is the moment to reimagine and transform, to escape the constraints of the past and design an entirely new kind of energy system. We have a once in a lifetime chance to fix this.

The Make or Break Decade

We are just over a year into the 2020s, the decade that will be defined by hard lessons and last chances. We either fix what’s wrong and find new paths forward, or bad gets worse. From climate change to public health to agriculture, there is no more wiggle room, no more runway, no more oil in the lamp. Our futures and those of every generation to follow will be shaped, and possibly derailed, by what happens next.

The good news is that there are still plenty of good answers and if we’re lucky, just enough time left to make a difference.

•••••••••••••••••

2020 opened with a blight: Covid-19, the first global pandemic in a century. 2021 followed with a bang. And broken windows. And a policeman beaten with an American flag. And a rabid mob storming the Capitol building.

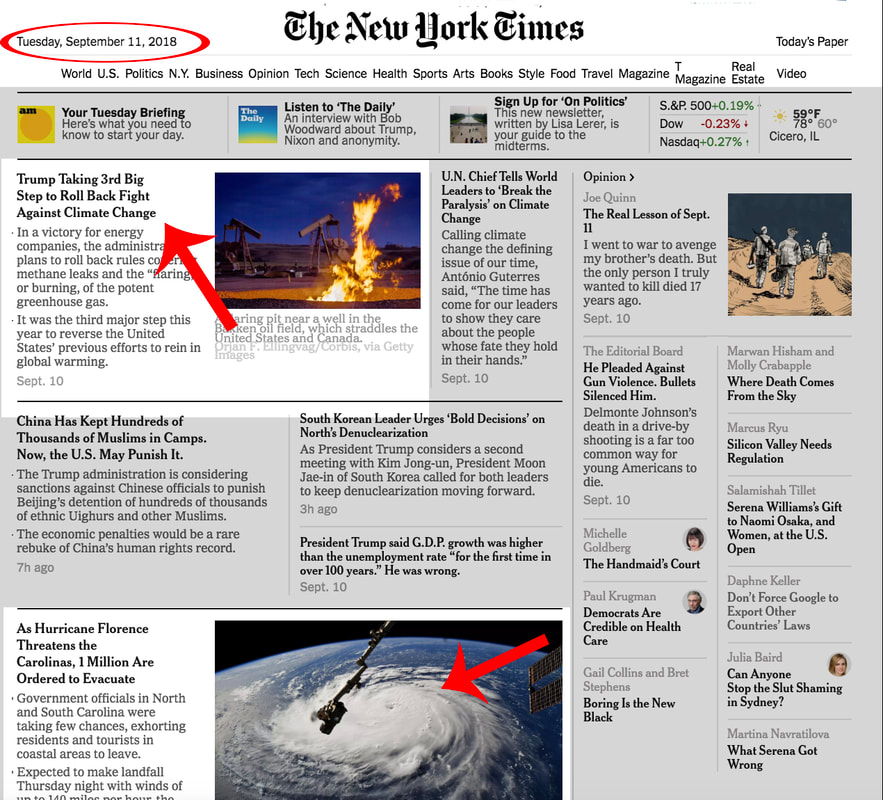

Five weeks later, and a “polar vortex” for the record books brings frigid air all the way south to Texas and nearly breaks the state’s electric grid. Although cold snaps are rare in Texas, they are not unprecedented. The damage was both predictable and predicted.

But the truth is that the entire US grid is in trouble, earning a dismal “D+” from the American Society of Civil Engineers. The towers and transmission lines, designed to last 50 years, are now well into their 60s, held together with proverbial duct tape. Factor in the wear and tear from weather ginned up by climate change (extreme rains, record droughts, bigger hail, colder cold snaps, hotter heat waves) and we are stuck in a cycle of pricey, emergency patchwork repairs.

Future Past

It isn’t only a matter of structural decay. The grid wasn’t designed for the digital age. Even the most visionary engineers of the 1950s and '60s couldn’t have imagined that there would be an internet or that it would require lots of energy-intensive “server farms” to operate. They didn’t plan for streaming video. Or online shopping. Or social networks. Or AI, which requires massive amounts of computing power, which takes us back to server farms. How do you grow a modern economy — how do you innovate — with a grid already stretched to its limits?

The American grid is a vision of the future, circa 1900. Thomas Edison oversaw construction of the world’s first grid, built in New York in the 1880s. When he flipped a switch in his friend J.P. Morgan’s office, hundreds of his patented incandescent light bulbs flickered in the Age of Electricity. Over the next few decades, battles were fought over whether power should be delivered as direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC), while small local grids linked together to form more efficient regional grids.

Still, forty years later in the 1920s electricity accounted for only 10% of the US energy supply. The rest was provided mostly by wood, coal, gas, and oil. There simply wasn’t that much to plug in. Iceboxes kept food cool with ice. Coal was shoveled directly into home furnaces for heating, and wood or coal into stoves for cooking. Clothes were washed with hand-cranked wringers and hung out to dry on clotheslines.

In the depth of the Great Depression a decade later, FDR’s Rural Electrification Act provided the economic incentive to extend the nation’s network of power lines to the 25% of the American population living on farms. Finally, after just about everyone everywhere had an electrical outlet, inventors got to work, electrifying everything. Toasters. Coffee pots. Stoves. Washers. Driers. Refrigerators. Hair curlers. Shavers. Street lights. Even blankets. And as we all learned from Texas, water pumps, too. Electricity was a game changer. It made the world modern. It was, quite literally, energizing.

Power PlayDespite years of warnings that a cold snap could trigger a catastrophic failure of the grid in Texas, those in a position to do something deliberately did nothing. They convinced themselves and everyone else that the risk was vanishingly small. And if that sounds suspiciously like the story of the Three Little Pigs, it basically is. If you don’t want your house to blow down, you have to prepare for the worst.

The energy companies, however, did take the time to work out the fine print of who exactly would foot the bill in a crisis: the customer. Likewise, the customer would be on the hook for any damage caused as a result of a power outage.

Estimates for the hundreds of thousands of insurance claims that have already been filed is in the tens of billions of dollars. But even those fortunate enough to be insured will likely face significant out-of-pocket expenses and months or longer of repairs.

Of course, no one thought that children would freeze to death, or that people would be forced to harvest snow to flush their toilets when the power went down in Texas. No one realized how quickly “modern” could disappear.

••••••••••••••

But that didn’t keep energy companies from making the most of the moment. When pipelines froze, it cut the supply of natural gas to power plants at the precise moment that demand for electricity spiked. In a matter of hours wholesale natural gas prices soared from about $3 per btu to over $1000. The utilities, desperate to keep the grid from completely collapsing, were at the mercy of the energy suppliers, so they paid. And then they immediately passed along the higher costs to customers with variable rate plans tied to wholesale gas prices. Normally, price fluctuations are minimal so these customers often save money over those who opt for fixed rate plans. But in this extraordinary, if predicted, crisis utility bills that were typically hundreds of dollars per month skyrocketed to thousands of dollars. Not only did customers freeze, but they paid for the pleasure.

The Texas legislature is working on a band-aid bill to help consumers, but the legislators are the ones who set the rules in the first place. If the power providers are forced to absorb the extra costs, they could go out of business, and their customers shunted to new providers who may charge higher rates. The only ones who appear to come out as winners are natural gas producers such as Comstock, whose CEO compared the unprecedented price surge to hitting the jackpot. Indeed.

•••••••••••••••••

If the low cost of energy was a point of puffed up Texas pride and a business draw before the blackout, it isn’t any more. After the cold, the floods and the mold come bankruptcies. Who wants to relocate to a state with a broken grid, lots of hurricanes, high insurance rates and not nearly enough plumbers?

Even in the best of times, blackouts are expensive. According to the US Department of Energy, power outages cost US businesses $150 billion annually. That’s $1.5 trillion over a decade. And that figure is likely rising as we become ever more dependent on server farms so critical to making our increasingly internet- and AI-dependent lives possible.

That is money, as they say, down the drain.

A Glow in the Dark

But not everybody lost power when the Texas grid shivered to a halt. The lucky owners of Tesla Powerwalls — large, sleek, expensive lithium batteries with enough juice to run a house — posted videos on social media of their homes, the only ones in the neighborhood with the lights on. Paired with a Tesla solar roof, which can still generate power on a cold, overcast day, these Powerwalls meant being able to ride out the nasty weather in style, with no fear of burst pipes — or hypothermia. That said, the the cost of charging up a Tesla car, which requires a grid plug-in, jumped from $25 to $900. Life in the Tesla lane was great so long as you stayed put.

The cost of a Powerwall is roughly $10,000 before installation, but that looks like a bargain compared to a surprise $17,000 electric bill, or the money spent and time lost to repair flood damage. Those with Power Walls could also find themselves getting breaks on insurance because they present a lower risk. When the power stays on pipes don’t freeze, so are less likely to burst.

Powerwalls have also proven their mettle for grid-level storage. In Australia a bank of Powerwalls (a Powerpack) installed four years ago to store energy from a wind farm quickly proved its worth by also preventing a blackout. When sensors detected a power drop in the grid, the batteries began discharging electricity directly into the grid, making up the difference. Now, utility companies in the US and around the world are ramping up the installation of battery back ups.

In fact, hundreds of companies are competing for this emerging, lucrative, market, experimenting with several different kinds of batteries and attracting considerable investor interest, even before Texas.

“When we get to roughly 20% of our peak demand available available in storage, we will be able to run a renewable-only system because the mix of solar and wind, geothermal and biomass all backed up with storage will be enough to carry us through even some of these potentially long lulls.” — Dan Kammen, UC–Berkeley, The Future of Energy Storage, CNBC (video)

Next Grid

While the US hobbles along with an aging grid designed for the 20th century, China is building a grid for the 21st. UHV (ultra high voltage) transmission is the key, making it possible to transmit electricity generated by wind farms and solar arrays (and coal, gas, hydroelectric and nuclear plants) over long distances without losing a lot of energy on the journey. This is how China can promise that the 2022 Olympics will be run completely on renewable energy.

UHV in at the heart of China’s plans to tie together its six regional grids into one supergrid — an expensive, complex undertaking with no shortage of challenges. Still, it points to a new, dramatic reimagination of how electricity can be efficiently transported at scale.

Electric grids aren’t limited by national boundaries. The Asia Super Grid project, which has been in development for the last decade, would link grids in China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, India and Russia. It is as much a diplomatic challenge as it is a technical one. Equally thorny is the issue of parts. Whoever controls component supply chains also controls, for all practical purposes, a grid — which quickly raises issues of national security.

It gets worse. According to former Google CEO and chair of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, Eric Schmidt, China is positioned to knock the US out of its top position as an AI superpower within a few years. A new report, describes the military implications, which are vast, ushering in new era of algorithmic warfare, complete with AI-controlled autonomous weapons.

Since AI requires abundant electricity to run massive amounts of calculations, whoever has the best grid wins.

Power is power.

••••••••••••

Assuming we manage to avoid a droid apocalypse, those nations able to provide a bounty of reliable, affordable and preferably renewables-sourced electricity will have the economic edge and a global competitive advantage.

In fact, they could control the bank. China’s emergence as a leader in cryptocurrency mining has everything to do with an abundance of cheap energy essential for running massive server farms. Now, through experiments internally with digital renminbi and internationally with cross-border digital yuan, China is positioning itself to set the standards and write the rules of digital finance.

Opportunity

The polar vortex finally returned to its polar home. Spring returned to Texas. And electricity and tap water have returned to most homes and businesses. But it would be mistake to return to the status quo.

This is the moment to rethink everything from engineering to policy. And it all begins, perhaps counter-intuitively, with voting rights. The collapse of the Texas grid was made possible — inevitable — by a catastrophic failure of leadership. Currently, there are several bills before the state legislature that would make it more difficult for people to vote, which as a rule gives incumbents an advantage. If there is to be any hope of bringing new thinking into the legislative mix, every citizen must be able to exercise her democratic right to vote. Those bills must be defeated.

Next, let’s look at the demand side of the equation. What if rebuilding were driven by metrics of energy efficiency? As Amory Lovins, co-founder of Rocky Mountain Institute, has often noted, the cheapest watt is the one you don’t need to buy. He calls them “negawatts,” with the savings going directly into customer pockets. Money that is not needed to pay electric bills is money that can be spent on other things. And often the money is spent locally, which means energy efficiency is good for local economies.

Likewise, reduced demand means electricity can be redirected elsewhere (see server farms); also, that fewer, pricey, fossil fuel-dependent central power plants may be needed, speeding the transition to renewables.

Less energy needed, lower bills, reduced capital costs: Less isn’t only more, it’s better.

Next on the list: energy generation. Even in frigid temperatures, most of the Texan wind turbines worked. If they had been properly winterized, all of them would have worked. The cost of grid solar and wind is now competitive, and sometimes cheaper, than that of coal and natural gas. Solar and wind farms are already cheaper to build than coal or natural gas plants, and can be expanded simply adding more solar panels and wind turbines. The “feedstocks”— sunshine and wind — are delivered free, no rail cars, trucks or pipelines required.

•••••••••••••••••••

To properly analyze the costs and benefits of various options requires systems thinking. ROSI™ (Return on Sustainability Investment) is a methodology developed at the NYU Stern School of Business to help companies better understand the financial value of environmentally aligned practices. Some examples are straightforward: Better waste management saves money. Others are less obvious. For example, ROSI™ puts a value on automotive recalls, so if sustainable practices lead to fewer recalls, that benefit can be understood in terms of the bottom line.

Something similar could be developed for designing a grid. Since wind and solar don’t rely on supporting infrastructures of rail and pipeline, they themselves are more reliable. Since sun and wind are free, production isn’t subject to the ups and downs of commodity markets. When paired with grid-level battery storage, they can supply power 24/7. And, of course, they do not emit CO2, which means that producing electricity by wind and solar will never be subject to the added cost of a carbon tax. Instead, they can generate income as a carbon credit.

There are also costs to be considered: Old solar panels are starting to pile up in landfills, creating a new category of waste. Although it is a problem that pales in comparison to the clear and present danger of the carbon pollution, it is a problem in need of a solution.

•••••••••••••••••••

As the costs of wind and solar generation continue to decline, hydrogen, which can be made using these renewables to power a process called electrolysis, may soon be another viable option. “Green” hydrogen can act as a battery (a way to permanently capture energy generated by intermittent solar and wind), or as feedstock to generate electricity using a fuel cell.

Breakthroughs in hydrogen storage such as PowerPaste could be game-changing. This molecule-trapping material is made with magnesium, an abundant and cheap mineral. A prototype factory is currently under construction in Germany, with trials planned later this year with small vehicles and drones.

Flexibility

The big take-away is to design a system that is able to accommodate a variety of clean power options, including those still on the far horizon. This means thinking not only in terms of grid-level generation, but also hyperlocal generation such as rooftop solar, which could be tied into a Powerwall battery, or directly into the grid to be shared as needed.

Imagine a parking garage filled with plugged-in cars whose collective stored energy could be accessed by the grid in a crisis: The garage as giant Power Wall.

Now, add some UHV transmission so that electricity generated from wind farms in the Great Plains could be used in a city a half a continent away to power up those very cars in that very garage.

The future is not only about supergrids, but also microgrids. These are self-sufficient modules that can separate and operate independently of the big grid in a crisis. If there’s a power outage on the big grid (by accident or cyber attack) a microgrid can tap into locally-sourced power (e.g. rooftop solar) to keep things humming until everything is back on line. Think of it as a kind of Powerwall for a neighborhood.

None of these are new ideas. There are technological challenges, but mostly we already have the technologies. Implementation is more a matter of will than skill.

The 2020s, our decade of reckoning, still has plenty of hard lessons in store for us. But we can begin to move the trajectory away from all those scary tipping points. Instead of a legacy of squandered opportunities, we can build a resilient, reliable, equitable, green grid designed to slow climate change and enable the next generation of innovation. We can build a grid that supports and protects us. We can make sure that a child will never again freeze to death because the power goes out.

_____________________

@trackernews