If you grew up in Chicago, you know Bushman. Like the Cubs, the Lake, da Bears, tall buildings and knowing without a doubt that putting anything but mustard and relish on a Vienna Beef hotdog is simply wrong, Bushman (!), an orphaned Western Lowland Gorilla born in Camaroon, is part of the local lore. He came to the city in 1930, sold by a Presbyterian minister-cum-animal trader to Lincoln Park Zoo for $3500 (roughly $50,000 in today's dollars). For the next 20 years Bushman ruled as Chicago's very own, safely caged King Kong (and perhaps an inspiration for the 1933 film).

He was a celebrity with noted pitching abilities that were demonstrated through the spirited throwing of fruit and feces at photographers. Nonetheless when Bushman took ill in the summer of 1950 and it was thought he might die,120,000 people stopped by the zoo in a single day to pay their respects. The great ape rallied, but passed away six months later on New Year's Day.

The decision to resurrect Bushman via taxidermy for eternal "life" at the Field Museum seemed like a fitting honor. For decades the husk of Bushman has stared through the smoked glass of a museum case as literally millions of Chicago school kids rushed past, eager to see mummies, mammoths and dinosaurs, or to have lunch in the cafeterias just up the hall. I was one of those kids. I probably stopped by for a quick glance or to lay my child-hands atop the palms of Bushman's cast-bronze hands, mounted on a side display.

I never really gave Bushman more than a passing thought until a few days ago when I visited the museum with a plan to browse all the older, less razzle-dazzle exhibits (sorry, Sue, you marvelous T. Rex you, we'll meet again, soon...).

••••••••••••••••••

"There are now an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 gorillas left in the world and their numbers are decreasing," I read on the electronic display in front of Bushman's case. That wildly optimistic estimate belies the age of the display—perhaps 15 or 20 years old. The signage itself has become an artifact of history.

The current tally for both species of gorillas (Lowland and Mountain), including two subspecies (Cross River and Eastern lowland), hovers around 100,000. While the number of mountain gorillas is up 25% over the last ten years, that still accounts for only a thousand. The number of critically endangered Cross River gorillas is in the low hundreds.

It is profoundly disturbing to realize that a species with whom humans share an astonishing 98% of DNA is under siege by us. Gorillas are hunted for bushmeat, body parts and trophies. They have been made homeless by logging and ravaged by diseases, including Ebola.

••••••••••••••••••

I stared at the enormous portrait of Bushman on the wall next to the display. What a face! The painter brilliantly captured his personality, his him-ness. Who else could that be but Bushman?

I wondered how many gorillas lived in the wild when Bushman's mother was killed 90 years ago. No one really knows. Ninety years from now will there be any left?

Perhaps that's Bushman's legacy: to stare at us through unblinking facsimile eyes, his stuffed body proof not only that gorillas existed, but that this one existed.

It is too late for Sue, the T. Rex. Her species' moment on Earth was snuffed out by an asteroid 65 million years ago. But it is not too late for gorillas and all the other wildlife under siege. According to the recent Living Planet report from the World Wildlife Fund, populations of mammals, birds, fish and reptiles have been decimated over the last fifty years, reduced by nearly two-thirds largely as a result of human activity. We are the new asteroid, but it is still possible to change course.

••••••••••••••••••

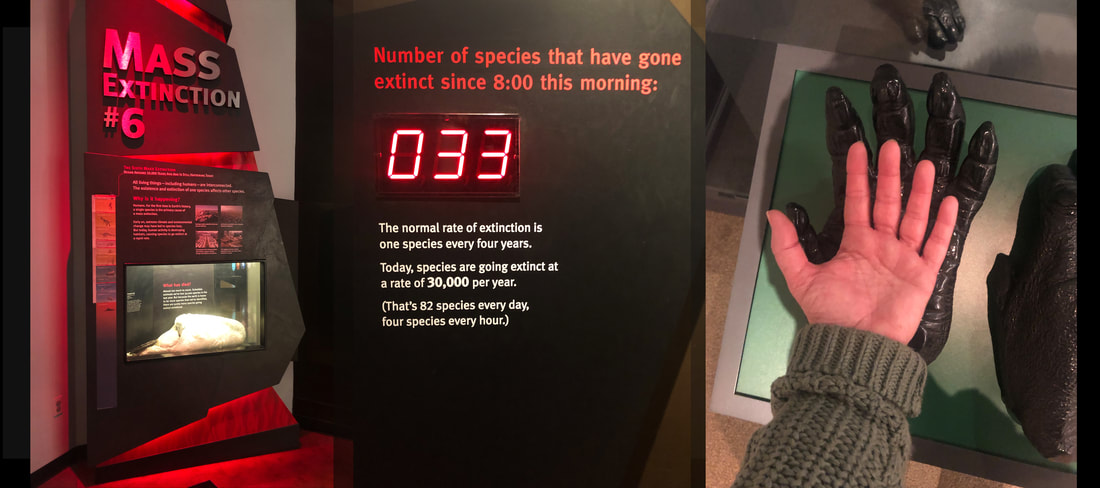

In another part of the museum, an exhibit on the planet's history of mass extinctions includes an extinction counter for the Sixth Great Extinction, which is currently underway. Species are now blinking out of existence at astonishing rate of 82 per day. That's 30,000 species vanquished annually. With apologies to architect Mies van der Rohe (who arrived in Chicago a few years after Bushman), sometimes less is less.

The digital counter was maddening. The numbers kept rising. How could I make a difference? How could I stop such a flood of death?

I put my now-adult hand in Bushman's palm and the abstractions faded away. Bushman died long before I was born, but time, space and evolution collapsed in our connection.

I still don't know how I can make a difference, only that everything depends on figuring it out. All of us. Together. For Bushman.

He was a celebrity with noted pitching abilities that were demonstrated through the spirited throwing of fruit and feces at photographers. Nonetheless when Bushman took ill in the summer of 1950 and it was thought he might die,120,000 people stopped by the zoo in a single day to pay their respects. The great ape rallied, but passed away six months later on New Year's Day.

The decision to resurrect Bushman via taxidermy for eternal "life" at the Field Museum seemed like a fitting honor. For decades the husk of Bushman has stared through the smoked glass of a museum case as literally millions of Chicago school kids rushed past, eager to see mummies, mammoths and dinosaurs, or to have lunch in the cafeterias just up the hall. I was one of those kids. I probably stopped by for a quick glance or to lay my child-hands atop the palms of Bushman's cast-bronze hands, mounted on a side display.

I never really gave Bushman more than a passing thought until a few days ago when I visited the museum with a plan to browse all the older, less razzle-dazzle exhibits (sorry, Sue, you marvelous T. Rex you, we'll meet again, soon...).

••••••••••••••••••

"There are now an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 gorillas left in the world and their numbers are decreasing," I read on the electronic display in front of Bushman's case. That wildly optimistic estimate belies the age of the display—perhaps 15 or 20 years old. The signage itself has become an artifact of history.

The current tally for both species of gorillas (Lowland and Mountain), including two subspecies (Cross River and Eastern lowland), hovers around 100,000. While the number of mountain gorillas is up 25% over the last ten years, that still accounts for only a thousand. The number of critically endangered Cross River gorillas is in the low hundreds.

It is profoundly disturbing to realize that a species with whom humans share an astonishing 98% of DNA is under siege by us. Gorillas are hunted for bushmeat, body parts and trophies. They have been made homeless by logging and ravaged by diseases, including Ebola.

••••••••••••••••••

I stared at the enormous portrait of Bushman on the wall next to the display. What a face! The painter brilliantly captured his personality, his him-ness. Who else could that be but Bushman?

I wondered how many gorillas lived in the wild when Bushman's mother was killed 90 years ago. No one really knows. Ninety years from now will there be any left?

Perhaps that's Bushman's legacy: to stare at us through unblinking facsimile eyes, his stuffed body proof not only that gorillas existed, but that this one existed.

It is too late for Sue, the T. Rex. Her species' moment on Earth was snuffed out by an asteroid 65 million years ago. But it is not too late for gorillas and all the other wildlife under siege. According to the recent Living Planet report from the World Wildlife Fund, populations of mammals, birds, fish and reptiles have been decimated over the last fifty years, reduced by nearly two-thirds largely as a result of human activity. We are the new asteroid, but it is still possible to change course.

••••••••••••••••••

In another part of the museum, an exhibit on the planet's history of mass extinctions includes an extinction counter for the Sixth Great Extinction, which is currently underway. Species are now blinking out of existence at astonishing rate of 82 per day. That's 30,000 species vanquished annually. With apologies to architect Mies van der Rohe (who arrived in Chicago a few years after Bushman), sometimes less is less.

The digital counter was maddening. The numbers kept rising. How could I make a difference? How could I stop such a flood of death?

I put my now-adult hand in Bushman's palm and the abstractions faded away. Bushman died long before I was born, but time, space and evolution collapsed in our connection.

I still don't know how I can make a difference, only that everything depends on figuring it out. All of us. Together. For Bushman.