There is the time before you know that it is actually possible to create custom pills with a machine inspired by a freestyle soda fountain and rest of your life when the brilliance of such an unexpected mashup of ideas becomes mainstream common sense. When Dr. Geoffrey Ling, a joyful polymath and serial entrepreneur whose long resume includes a stint as the Founding Director of the Biological Technologies Office (BTO) for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), explained the technology, the SRO audience at the TWIN conference in Chicago earlier this week burst into applause (followed by a rare standing ovation at the end of the talk). Ling is working to take the technology--developed at MIT under a DARPA grant— to market through a startup with an unusually to-the-point name for a drug company: On Demand Pharmaceuticals. This is just one of the many plates Dr. Ling has spinning at any given time. The audience, or at least I, felt brain cells exploding to keep up with it all.

"It is sobering to think think that when Mozart was my age, he'd been dead for two years," noted pianist and satirist Tom Leher.

It was kind of like that, only fortunately Dr. Ling will be with us for a long time, so I can look forward to feeling even less accomplished for years to come.

Like all the best ideas, made-to-order drugs have the potential to solve a range of problems from supplying military field hospitals with what they need when they need it (the DARPA challenge) to improving quality control and lowering prices in the civilian market (most generic drugs in the US are imported from China).

Go Dr. Ling!

"It is sobering to think think that when Mozart was my age, he'd been dead for two years," noted pianist and satirist Tom Leher.

It was kind of like that, only fortunately Dr. Ling will be with us for a long time, so I can look forward to feeling even less accomplished for years to come.

Like all the best ideas, made-to-order drugs have the potential to solve a range of problems from supplying military field hospitals with what they need when they need it (the DARPA challenge) to improving quality control and lowering prices in the civilian market (most generic drugs in the US are imported from China).

Go Dr. Ling!

ETUDES

| | | |

If Mozart were alive today, no doubt he would be jamming with Matthew Whitaker. At any age Whitaker's understanding and abilities as a musician would be impressive, but to see him at 17 in the early part what promises to be a long and storied career, what a treat.

Whitaker's performance was part of TWIN's Etudes for Innovation concert, a walk-the-talk (sing-the-song, tap-the-beat, dance-the-dance) master class in innovation. It is one thing to tell people to "think different," especially a room full of executives and business consultants, and quite another to get them to actually do it. Music goes where spreadsheets, post-its and mission statements can't, instantly rewiring mind and body, subtly altering perception in ways that make it easier to see possibilities, connections, solutions.

In short, to imagine how a soda machine can help solve a drug supply crisis, just add music (and dance and art).

Technically this was TWIN's first year (The World Innovation Network). The previous nine years the conference was hosted at Northwestern University and known as KIN (Kellogg Innovation Network) This then was the tenth Etudes concert. In 2016 I interviewed creative director Jeffrey Ernstoff for background (see video embedded above).

Whitaker's performance was part of TWIN's Etudes for Innovation concert, a walk-the-talk (sing-the-song, tap-the-beat, dance-the-dance) master class in innovation. It is one thing to tell people to "think different," especially a room full of executives and business consultants, and quite another to get them to actually do it. Music goes where spreadsheets, post-its and mission statements can't, instantly rewiring mind and body, subtly altering perception in ways that make it easier to see possibilities, connections, solutions.

In short, to imagine how a soda machine can help solve a drug supply crisis, just add music (and dance and art).

Technically this was TWIN's first year (The World Innovation Network). The previous nine years the conference was hosted at Northwestern University and known as KIN (Kellogg Innovation Network) This then was the tenth Etudes concert. In 2016 I interviewed creative director Jeffrey Ernstoff for background (see video embedded above).

THE WORLD INNOVATION NETWORK (TWIN)

Creating "the world innovation network" is as aspirational as it is inspirational at this point. Yes, people came from twenty countries, representing every continent, including (thanks to the Swan boys, Sir Robert and son Barney) Antarctica. Yes, "innovation" is mantra, mission and grail for the business executives, consultants, policymakers and scientists who filled the room. But for me the most compelling word is "network." In the few years that I have been part of KIN/TWIN, that has been the sweet spot—and how a small, thoughtful conference with global ambitions in the middle of the American Midwest manages to punch above its weight.

Rob Wolcott, a clinical professor in innovation and entrepreneurship at Kellogg, has the been the driving force of the conference from the start. Nothing delights him more than when 2 + 2 = 5, or maybe 6, or maybe more. When combinations prove greater than the sum of their parts, Rob's heart sings. "Never leave serendipity to chance" isn't only a trademark tagline but a mission for Rob, and by extension for TWIN as well.

It is a clever, mischievous turn of a phrase. Synchronicity—"the simultaneous occurrence of events that appear significantly related but have no discernible connection"— is defined by chance. Rob lives to tweak the odds in fate's fortuitous favor.

To coax serendipity out from the shadows and mix up the crowd from the get go, Rob orchestrates a remarkably effective exercise with a slightly grandiose title—"Share Your Vision, Change Our World"—on the first night of the conference, just before dinner. The crowd breaks into groups of four to six people who ideally don't know one another and take turns describing a project either in progress or just getting off the ground. Questions, suggestions and offers of connections are encouraged, but criticism is expressly forbidden. If you don't like someone's idea, you don't have to support it, but you don't tear it down. I found myself with a veteran marketer, a science museum strategist and a military technologist. In very short order, not only did we find all kinds of ways to help one another, but by defining ourselves through our passions, we also skipped past the usual resume banter to forge the beginnings of what in many cases could evolve into genuine friendships. "SYV, COW" is an exercise we would all do well to practice on a more regular basis. It's genius fun.

The Good and the Smart

I have been to too many conferences where somebody at some point steps up to a podium and says something deeply stupid about how the few hundred people in the room are the best and the brightest and that it is up to them (us) to solve the most world's intractable problems. If the future of the future rests in the hands of a few hundred people who can afford to attend a conference, we are surely doomed.

TWIN succeeds because although its ambitions are outsize, its approach is somewhat more humble. It brings together a smattering of the good and the smart, people who might not otherwise cross paths professionally or geographically and gives them the space to share what are often radically different perspectives. The view from Bangladesh, or from China, or Japan, or from Africa is different whether through the lens of business and investment (a popular one at TWIN) or culture (see Etudes, which this year also featured Yumi Kurasawa on koto and Irish tenor Ronan Tynan singing everything from Italian arias to pub songs).

Trust is a defining theme, but notably that doesn't agreement. Personally, I am not convinced that chip-enhanced "Humans 2.0," setting up mining operations on the moon, or bioengineering apples that never ever ever turn brown area such good ideas. But I am very interested in listening and talking to those who think they are. We both might learn something and through argument find deeper understanding and more nuanced solutions.

Beyond the Bubble

Before smart phones, it used to be easier to maintain a conference bubble. For a few days you could find yourself pleasantly island-ed with a group of semi-strangers navigating a jam-packed schedule of more-and-less interesting presentations, lavish meals and late night parties.

Now news constantly seeps in from the edges, all too often providing stark counterpoint to the optimism that usually dominates on stage. During the few days of TWIN, a US president was laughed at during a speech at the UN; a would-be Supreme Court justice went on a partisan, vitriolic rant on national television; space satellites photographed flood waters from Hurricane Florence on South Carolina shoreline nearly two weeks after landfall; the "easy to win" trade war with China continued to escalate; and the US government managed to use a report predicting a 7° F rise in temperature by the end of the century to justify the rollbacks of regulations limiting fossil fuel use.

A few hundred people at a conference, no matter how good or smart—or even best and brightest—can't fix any of that. But by talking, trusting, listening, connecting, challenging perspectives and being inspired by the works of others, it is possible to regain a sense of balance and leave with a restored sense of—to quote Amory Lovins—the power of applied hope.

"...The optimist treats the future as fate, not choice, and thus fails to take responsibility for making the world we want. Applied hope is a deliberate choice of heart and head. The optimist, says David Orr, has his feet up on the desk and a satisfied smirk knowing the deck is stacked. The person living in hope has her sleeves rolled up and is fighting hard to change or beat the odds. Optimism can easily mask cowardice. Applied hope requires fearlessness...."

Gems

My favorite parts of a conference are the gems you don't see coming. Sometimes they're in a presentation, but more often they emerge in casual conversation. For example...

• From Dante Lauretta, director of NASA's OSIRIS-REX asteroid mission, I learned that after years of navigating the through solar winds and gravitational tides of space, the ship will kiss the asteroid, landing for a mere five seconds before beginning its journey home. By the time it completes its round trip back to Earth, Dante's eldest son, who was born a few years after planning for the project began, will be in college. Space meet Time...

• From Alexandre Roulin, who studies ecology and evolution at the University of Lausanne, I learned that the social lives of barn owls are deeply complex, often scandalous and boundary-busting. Also, when the enemy of your enemy is a vole, there can be peace in the Middle East.

• From Andreas Caduff, CEO of Biovotion, a Swiss company that designs medical wearables, I saw the potential for body sensors to be used for real-time public health studies, which could be especially useful for monitoring people living downstream or downwind of coal plants and other sources of pollution.

• From Brian Collins, head of the eponymous branding and design firm COLLINS, I reveled in the details of how much ahead-of-her-time and fearless Amelia Earhart truly was (when the presentation video is available, I'll post it here).

• From Safi Bahcall, physicist, technologist and author of the soon-to-be published book Loonshots, I heard—via impromptu lunch-table lecture—fascinating tales of how the US became a research powerhouse after WWII.

Rob Wolcott, a clinical professor in innovation and entrepreneurship at Kellogg, has the been the driving force of the conference from the start. Nothing delights him more than when 2 + 2 = 5, or maybe 6, or maybe more. When combinations prove greater than the sum of their parts, Rob's heart sings. "Never leave serendipity to chance" isn't only a trademark tagline but a mission for Rob, and by extension for TWIN as well.

It is a clever, mischievous turn of a phrase. Synchronicity—"the simultaneous occurrence of events that appear significantly related but have no discernible connection"— is defined by chance. Rob lives to tweak the odds in fate's fortuitous favor.

To coax serendipity out from the shadows and mix up the crowd from the get go, Rob orchestrates a remarkably effective exercise with a slightly grandiose title—"Share Your Vision, Change Our World"—on the first night of the conference, just before dinner. The crowd breaks into groups of four to six people who ideally don't know one another and take turns describing a project either in progress or just getting off the ground. Questions, suggestions and offers of connections are encouraged, but criticism is expressly forbidden. If you don't like someone's idea, you don't have to support it, but you don't tear it down. I found myself with a veteran marketer, a science museum strategist and a military technologist. In very short order, not only did we find all kinds of ways to help one another, but by defining ourselves through our passions, we also skipped past the usual resume banter to forge the beginnings of what in many cases could evolve into genuine friendships. "SYV, COW" is an exercise we would all do well to practice on a more regular basis. It's genius fun.

The Good and the Smart

I have been to too many conferences where somebody at some point steps up to a podium and says something deeply stupid about how the few hundred people in the room are the best and the brightest and that it is up to them (us) to solve the most world's intractable problems. If the future of the future rests in the hands of a few hundred people who can afford to attend a conference, we are surely doomed.

TWIN succeeds because although its ambitions are outsize, its approach is somewhat more humble. It brings together a smattering of the good and the smart, people who might not otherwise cross paths professionally or geographically and gives them the space to share what are often radically different perspectives. The view from Bangladesh, or from China, or Japan, or from Africa is different whether through the lens of business and investment (a popular one at TWIN) or culture (see Etudes, which this year also featured Yumi Kurasawa on koto and Irish tenor Ronan Tynan singing everything from Italian arias to pub songs).

Trust is a defining theme, but notably that doesn't agreement. Personally, I am not convinced that chip-enhanced "Humans 2.0," setting up mining operations on the moon, or bioengineering apples that never ever ever turn brown area such good ideas. But I am very interested in listening and talking to those who think they are. We both might learn something and through argument find deeper understanding and more nuanced solutions.

Beyond the Bubble

Before smart phones, it used to be easier to maintain a conference bubble. For a few days you could find yourself pleasantly island-ed with a group of semi-strangers navigating a jam-packed schedule of more-and-less interesting presentations, lavish meals and late night parties.

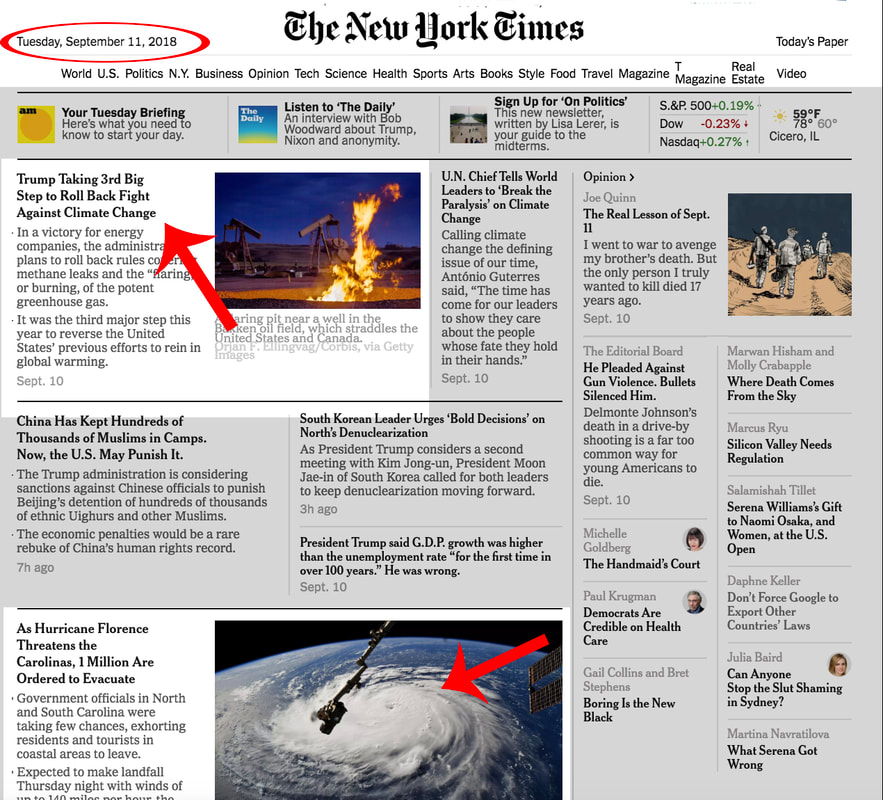

Now news constantly seeps in from the edges, all too often providing stark counterpoint to the optimism that usually dominates on stage. During the few days of TWIN, a US president was laughed at during a speech at the UN; a would-be Supreme Court justice went on a partisan, vitriolic rant on national television; space satellites photographed flood waters from Hurricane Florence on South Carolina shoreline nearly two weeks after landfall; the "easy to win" trade war with China continued to escalate; and the US government managed to use a report predicting a 7° F rise in temperature by the end of the century to justify the rollbacks of regulations limiting fossil fuel use.

A few hundred people at a conference, no matter how good or smart—or even best and brightest—can't fix any of that. But by talking, trusting, listening, connecting, challenging perspectives and being inspired by the works of others, it is possible to regain a sense of balance and leave with a restored sense of—to quote Amory Lovins—the power of applied hope.

"...The optimist treats the future as fate, not choice, and thus fails to take responsibility for making the world we want. Applied hope is a deliberate choice of heart and head. The optimist, says David Orr, has his feet up on the desk and a satisfied smirk knowing the deck is stacked. The person living in hope has her sleeves rolled up and is fighting hard to change or beat the odds. Optimism can easily mask cowardice. Applied hope requires fearlessness...."

Gems

My favorite parts of a conference are the gems you don't see coming. Sometimes they're in a presentation, but more often they emerge in casual conversation. For example...

• From Dante Lauretta, director of NASA's OSIRIS-REX asteroid mission, I learned that after years of navigating the through solar winds and gravitational tides of space, the ship will kiss the asteroid, landing for a mere five seconds before beginning its journey home. By the time it completes its round trip back to Earth, Dante's eldest son, who was born a few years after planning for the project began, will be in college. Space meet Time...

• From Alexandre Roulin, who studies ecology and evolution at the University of Lausanne, I learned that the social lives of barn owls are deeply complex, often scandalous and boundary-busting. Also, when the enemy of your enemy is a vole, there can be peace in the Middle East.

• From Andreas Caduff, CEO of Biovotion, a Swiss company that designs medical wearables, I saw the potential for body sensors to be used for real-time public health studies, which could be especially useful for monitoring people living downstream or downwind of coal plants and other sources of pollution.

• From Brian Collins, head of the eponymous branding and design firm COLLINS, I reveled in the details of how much ahead-of-her-time and fearless Amelia Earhart truly was (when the presentation video is available, I'll post it here).

• From Safi Bahcall, physicist, technologist and author of the soon-to-be published book Loonshots, I heard—via impromptu lunch-table lecture—fascinating tales of how the US became a research powerhouse after WWII.

ETHICS

For the last couple of years (although not this year) I put together a compendium ("KINpendium") of videos, biographies, bibliographies and essays from the conference in an attempt to a create a contextualized reference. The process required watching all the videos and taking notes. Several of the presentations really resonated and stayed with me.

Throughout TWIN, in part due to all the outside news seeping in via cellphone, I kept thinking about a conversation between Rob and Zan Boag, editor of New Philosopher magazine, last year:

"I think we need to stop. We need to reflect not on what we can do, but what we should do... These days there are so many of us with such powerful tools that we're able to effect great change upon the world. So we have a responsibility not just for those living with us now, but a responsibility to those who are going to be born after us."

It is easy to get so dazzled by technological potential that the downsides can't been seen until, of course, they can. Zan's warning came months before the Facebook / Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, a data manipulation that compromised the integrity of the 2016 election with ramifications that will be felt for decades to come.

Steve Jobs' dictum to "think different," so inspiring two decades ago, now rings hollow. We have to do better, much better. We have to be better. We have to insist on better.

The kinds of serendipitous conversations and connections that can happen at a conference such as TWIN are more important than ever. This year's theme—"Horizons"—was meant to evoke a sense of possibility and exploration, but there are dark and dangerous clouds closing in from all sides. It is going to take a global network of innovators (a TWIN), or even better yet a network of networks (TWIN's twins' twins...), to get through this.

Serendipity, here's your chance.

Throughout TWIN, in part due to all the outside news seeping in via cellphone, I kept thinking about a conversation between Rob and Zan Boag, editor of New Philosopher magazine, last year:

"I think we need to stop. We need to reflect not on what we can do, but what we should do... These days there are so many of us with such powerful tools that we're able to effect great change upon the world. So we have a responsibility not just for those living with us now, but a responsibility to those who are going to be born after us."

It is easy to get so dazzled by technological potential that the downsides can't been seen until, of course, they can. Zan's warning came months before the Facebook / Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, a data manipulation that compromised the integrity of the 2016 election with ramifications that will be felt for decades to come.

Steve Jobs' dictum to "think different," so inspiring two decades ago, now rings hollow. We have to do better, much better. We have to be better. We have to insist on better.

The kinds of serendipitous conversations and connections that can happen at a conference such as TWIN are more important than ever. This year's theme—"Horizons"—was meant to evoke a sense of possibility and exploration, but there are dark and dangerous clouds closing in from all sides. It is going to take a global network of innovators (a TWIN), or even better yet a network of networks (TWIN's twins' twins...), to get through this.

Serendipity, here's your chance.