|

The Janet A. Ginsburg Chicago Tribune Collection is available for research at Michigan State University Libraries.

|

|

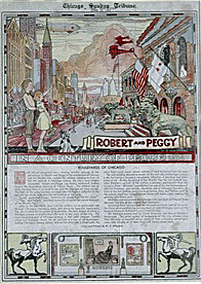

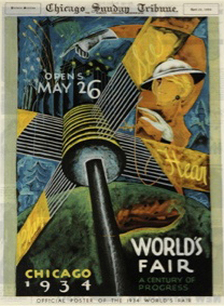

This drawing was one of a series of twelve illustrations that ran in the comics section of the Chicago Tribune throughout the summer of 1933. It charted the adventures of a little boy and his sister at the Century of Progress World’s Fair. Note the zeppelin and airplanes flying overhead and the billboard-size digital clock—all symbols of 20th innovation and the bright future to come.

The series was written and drawn by Professor William Garrison Whitford, who taught Art Education at the University of Chicago. The 1933 World's Fair was a rare ray of hope in the midst of the Great Depression and was so successful, it was kept open for an extra year.

Advertising was far more profitable for newspapers than income generated from paper sales, so prices were slashed to pump up circulation.

In 1926, nearly three-quarters of newspapers published in cities with populations between 25,000 and 100,000—the majority of American newspapers in the majority of American cities—charged 3 cents or more a copy. That would be the equivalent today of about a quarter. Only about 20% sold for as much as a nickel. But intense competition kept newsstand prices lower in Chicago, where the 2 cent price prevailed from the turn of the century well into the 1940s. A former practice newsroom for student broadcasters in the basement of Northwestern's journalism school was converted into a space where I could sort through hundreds of vintage newspapers.

|

by J. A. Ginsburg

DIAMOND IN THE ROUGH It was a chance encounter. Zipping through a roll of microfilm in the Chicago Tribune's news library one day, I came across an illustration from the 1933 World's Fair: Robert and Peggy in a Century of Progress. It was one of a dozen serialized stories about a little boy and his sister and their adventures at the Chicago Fair. Despite scratches and low-quality black-and-white reproduction, it was clearly a treasure. I made a photocopy and began asking around to see whether anyone might still have the actual newspaper. The Tribune's resident archivist, retired journalist John McCutcheon—the son of the Pulitzer-winning cartoonist of the same name—was intrigued: “This is beautiful! If you can find it, we’d sure love to have it!" Which, of course, meant that he didn’t have it and didn’t know any more about it than I did. Microfilm had become popular during the 1970s and 80s and almost every major newspaper, including the Chicago Tribune, tossed out archives. Replacing floor to ceiling stacks of musty old paper with small, lightweight rolls of film seemed like a genius move. By the time microfilm's shortcomings became apparent (the plastic substrate deteriorated, it didn't reproduce color, difficult to view a page in its entirety) the originals were long gone. The Tribune’s lost treasure was more of a loss than most because many of the tossed volumes were rag editions that had been printed on special low-acid paper intended for long term storage. The Tribune—a company that helped define vertical integration—was in a unique position to indulge in fancy, pricey archiving. It owned forests and paper mills in Canada, as well as an ink plant, linotype machines, printing presses, delivery trucks and, of course, a newsroom full of deadline-crazed reporters, artists, and photographers. The paper’s tagline unabashedly proclaimed the Chicago Tribune to be the “World’s Greatest Newspaper.” (In 1977, a staff designer killed the famous phrase with an expert flick of his exacto knife. Today, it lives on as “WGN,” the call letters of the company’s radio and television stations). In 1937, as part its centennial celebration, the paper ran a series of ads detailing its multi-faceted brilliance for eager readers. One ad —“How You Get Your Tribune”—provided an info-graphic cutaway of Tribune Tower, revealing the logistical secrets of an ultra-modern high rise newspaper factory, albeit one sheathed in limestone, complete with gothic gargoyles.: “The eleventh home of the Chicago Tribune, the present Tribune building, is the first to be specially designed for the production of newspapers and nothing else. From the cartoonists happily drawing in their aerie at the top of the Tower (Dick Tracy enjoyed a prime Lake view) to an underground tunnel for transporting enormous rolls of newsprint, the building was a vision of 20th century efficiency.

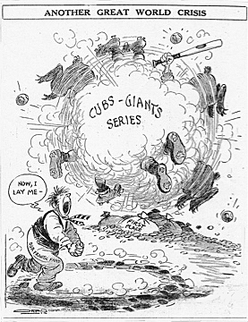

I envy the reporters of that era, who could literally feel the building shake with urgency when presses roared to life in the basement. From notebook to typewriter to linotype to plate to press to trucks to newsboys on street corners and papers flung onto neighborhood lawns, the news was news. A CUBS WIN... News librarians really do know it all. And it was in the Tribune library, which everybody called "the morgue," that I finally snagged the lede I was hoping for: a hot tip about an airplane pilot with a taste for old sport pages and remarkable timing. In 1981, the Tribune Company bought the Chicago Cubs baseball team, sparking considerable corporate interest in Cubs history. I am still not quite sure how Bill, the American Airlines pilot, came into the Tribune picture. Or why his knowledge of the Cubs’ past would have been considered any better or deeper than that of the paper’s own sportswriters. But there he was, in the right place at the right time to save decades’ worth of vintage newspapers from a landfill fate. I found Bill in a western suburb, where he took me to see the papers, now safely tucked away in storage lockers. There were impressive runs of most of the major dailies—stacks so high, in fact, we climbed around them like goats. The Tribune run was unusually good, both for its condition and size. Ironically, Bill’s hobby of cutting out old sports pages for collectors, made it possible for someone like me to think about creating an exhibit. A pristine archive must be kept pristine. Bill gave me a few dozen pages, including some Robert & Peggy illustrations, which I used to create a portfolio to try to drum up interest. LET'S PUT ON A SHOW! It took several years, but once funding was secured—a $10,000 grant from the Illinois Arts Council, the largest possible in its category—I needed to find space to curate a show. Older news pages are large and delicate and there were a lot of them. To the rescue came Dick Schwarzlose, a much-adored professor and assistant dean at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism. Dick, who loved old newspapers far more than he cared about bureaucracy, snuck me into a recently vacated room in the basement of Fisk Hall (Medill has since moved to a new building next door). Since my presence wasn’t strictly official, Dick asked me to keep a low profile, then proceeded to send a steady stream of professors and graduate students to my secret lair for sneak peaks. It was a fabulous space, whose previous incarnation was as a pretend television news set for would-be pundits to practice. I set up my work table in the “anchor spot” beneath foam-core call letters of the faux station. Bill very kindly trucked over a literal ton of material and I was finally ready to get to work. I had no idea what I was doing. I wasn’t even entirely sure that there was a show to be mined from these mountains of old newspaper pages, despite what I had written in the grant proposal. I had only skimmed the surface of Bill’s collection at the storage locker. Still, it was comforting to know that no matter what terrible thing I might inadvertently do, at least I was keeping the vintage pages out the garbage, which is where they had been headed. Bill was interested only in sports pages (many of which, by the way, can be seen on display at Harry Caray's restaurant). I tried my best to figure how to do the right thing. I was careful to mark sections from which pages were removed, and never ever ever cut up an individual page. Slowly but surely, I worked through stacks of bound volumes and other miscellaneous material Bill sent along, creating categories as I sorted, filling up hand-made cardboard bins for further editing. It was a treasure hunt of the very best sort. (continue to page 2) |