Adding insult to injury, according to Al Jazeera, money from illegal logging near the Afghan border in Malakand found its way into the pockets of the Taliban. And in a literal cascade of bad to worse, the ill-gotten timber, stashed temporarily in ravines, magnified the destructive power of the flood-waters, shredding bridges and roads in the hurtle down river.

When the waters eventually recede, an eroded landscape will emerge. Whatever fertility the ground held will have been leached away, much of it to end up as mucky silt, clogging Pakistan’s over-extended, under-maintained massive irrigation network.

| | |

Although the scars are local and downstream effects regional, the impact is actually global.

Take, for example, Pakistan’s role as the world’s fourth largest producer of cotton, generating roughly 10% of global supply. Since this year’s crop is a literal wash out, the 2010 global harvest won’t meet demand. The situation is that much more serious, considering that even minus Pakistan’s contribution, the harvest will be larger than last year’s, coming in at 100 millions bales. Increased demand from an ever-growing global population will translate to a 4 million bale shortfall, according to analysts. That means cotton prices are going up for everybody everywhere.

Next year, when you pay more for jeans, blame the Taliban…

(added 10/4/10: “Cotton Clothing Price Tags to Rise” / New York Times)

HOW MORE BECOMES LESS

Global supplies are also tight – and prices rising – for other commodities. What began as a season full of bumper crop predictions turned to whole wheat toast in the heat of Russia’s bumper drought, and mush in the wake of Canada’s floods. Supplies aren’t expected to ease until the end of 2011, the earliest a temporary Russian export ban may be lifted.

From corn to rice, and fish to fruit, the era of easy surpluses is over. Any glitch almost anywhere in the weather, or disease outbreak, insect infestation, pollinator decline or oil spill can send ripples throughout the global food network.

“Despite record harvests beteeen 2000 and 2007, the world ate more food than it produced. Back in 1998, human beings grew 1.9 billion tons of cereals and ate 1.8 billion tons of them. Since then yields have risen, but so have our appetites, and there’s a disjoint between the two. In five of the last ten years, the world consumed more food than farms have grown, while in a sixth year we merely broke even. Reserves are bottoming out. Even without a climate trigger, the ledger shows some unpleasant mathematics.”

- Empires of Food

This is hardly the first time this sort of thing has happened. In their new book,Empires of Food: Feast, Famine, and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations, Evan D. G. Fraser and Andrew Rimas write with breezy style and depressing detail of how food networks throughout history have crashed for utterly predictable, if not always completely preventable, reasons.

They point to four fraught assumptions:

- Soil is fertile: Unless carefully managed, it won’t stay fertile. Fertility “bumps” from planting on newly deforested areas are temporary. Chemical fertilizers are addictive: The more you use, the more you need. Also, much is lost in farm field run off, which knocks nature’s balance out of whack as it moves downstream (e.g., algal blooms that lead to marine “dead zones”). Fertilizers and pesticides also take a toll on soil’s natural microfauna, further affecting fertility.

- Weather is good: Civilizations tend to flourish when the weather is predictable, with nice long growing seasons. But climates change, with or without man-made greenhouse gases to goose the process along. A drop of one degree in Europe’s average temperature during the 16th century was enough to tip the Little Ice Age. “While such aberrations may seem piffling, if spring temperatures drop by just half a degree, the growing season can shrink by ten days.”

- Specialization is smart business: Monocultures are more vulnerable to disease and predation. A food network of monocultures is only as strong as its weakest link. “…(S)ince all our specialty food patches depend on one another to constitute our food empire, none of them can exist alone.”

- Energy is abundant and cheap: From fossil fuels used in chemical fertilizers, to fuel for tractors, trucks, trains, ships and planes and electricity for refrigeration, the cost of modern food is wedded to the cost of energy. Oil prices rise and food prices follow. If they spike, expect food riots, such as those seen in 2008, despite record-breaking harvests. “The weight of the global breadbasket was 2.24 billion tons, a robust 5 percent increase over the previous year. Yet food prices utterly detached themselves from the fact that we had reaped the best harvest in the entirety of human existence.”

To be mistaken in one colossal assumption about our food empire may be a misfortune. To be mistaken in all four seems like something worse than carelessness. It seems like willful disregard for the truth. When we finally shed these assumptions, we’ll realize the genuine price of the way we produce, distribute, and consume food.

Fraser and Rimas tell a cautionary tale from the Middle Ages that offers particularly striking parallels the present. A thousand years ago, monasteries sat atop a vertically integrated food network that would have been the envy of any modern transnational conglomerate. The monks had money to invest in innovative technology (the moldboard plow), which provided an unbeatable advantage over small farmers, who found themselves with no choice but to move to cities. The monks also had to clout to control processing (royal licenses for milling) and become gatekeepers for distribution (royal licenses to run market fairs). But even such divinely-blessed productivity wasn’t to last.

More than temporal success, the most striking impact that the Cistercians had on Europe was that they chopped down all the trees. …(R)eal estate in Europe had gotten expensive. Even marginal land, bits of scrub and hilltop, needed to come under the plow to feed the growing markets in the cities. Since chopping trees and tilling hilly ground is a sure means of exhausting and eroding soil, over time, the harvests worsened. The monks kept pushing their farms outward, even plowing uplands that once pastured sheep and cattle – animals whose digestive systems had done an effortless job of fertilizing the earth. With the loss of livestock’s manure and the added cultivation, the ground blew and washed away even quicker…

…By the end of the thirteenth century, margins between supply and demand had thinned to a razor’s breadth. A decline of 10 percent in a year’s harvest spelled hunger; a loss of 20 percent of the harvest meant famine.

…And then the financial system imploded. For centuries, bankers in Siena had loaned heavily to Europe’s royal houses, financing wars and armies. They overextended themselves on architecture, cavalry, and crusades, so when the harvests dropped and manors or cities defaulted on their loans, the banks collapsed. In 1298, the Gran Tavola bank of the Bonsignori, the Rothschilds of their day, failed. Rents soared as landlords struggled to pay their debts. Work on Siena’s great cathedral came to stop…”

For most of Europe. the crisis truly began with a midsummer storm in 1314. It rained too much and for too long, drumming flat the ripening crops and rotting them on the stalk. The grain harvest proved both late and short, and the next year was worse. Dikes collapsed, the sea engulfed the fields and pasture, and an epidemic carried by Mongol raiders, possibly anthrax, managed to snuff out much of the continent’s livestock. In England, the price of wheat jumped eightfold. In 1316, it rained again, and Europe toppled into the worst famine in its history.

By some estimates, 10% of Europeans starved to death that year.

CENTURY OF THE CITY

Can we learn from the monks’ mistakes? Or is the tragedy of Pakistan a sign of things to come? From Haiti to Guatemala to Borneo, deforestation has amplified the effects of natural disasters, yet planting trees is rarely, if ever, part of comprehensive aid packages.

Stanford economist Paul Romer tells of looking out a plane window while flying over Africa and seeing plenty of “uninhabited” land, perfect for “charter cities.” These are settlements built from scratch, based on rules designed to “provide security, economic opportunity, and improved quality of life.” These rules of men, however, show a breathtaking obliviousness to the rules of nature. Land empty of people doesn’t mean it is uninhabited, or that is doesn’t provide key services. Wetlands, flood plains, forests – all have great value for people. But their value is tied up in costs avoided (storm damage, pollution-related expenses), which are always more of a challenge to slot into a spreadsheet for investors.

To help make his case, Romer shows a graphic that visualizes all the arable land on Earth as a series of identical dots. The planet’s 3 billion city-dwellers take up only 3% of the dots. Add another billion living in proposed charter cities and it is 4%. Which sounds like a pretty reasonable deal, but, of course, the dots are not identical. Some land is good for wheat, other for rice. Some is ruined for a season by flood or drought, or just plain marginal. Some dots are former forests that have been slashed and burned to make way for biodiversity-busting palm oil plantations. More people means we probably need more dots of arable land, not fewer. And as for wildlands that help nourish and provide water for the arable lands that feed the people in cities? Dot-less.

NODES & NETWORKSLikewise, the truth behind the much-touted efficiencies of scale that make dense cities “greener” than car-dependent suburbs can get a little messy. “Green-ness” isn’t only about whether people walk or drive to stores, but also a function of how “green” the products and services they purchase may be, shipping included (which is why hybrid cars, loaded with globe-trotting battery components, aren’t quite as eco-friendly as billed). A true urban footprint extends as far as the trade routes used to bring in the goods that keep a city going. By that definition, almost every city is now a global city.

Boundaries are further blurred as urban areas merge and sprawl into megacities. In a sense, cities have become nodes of a single globe-spanning “supra-urban” network.

It will take systems thinking – preferably ecosystems thinking – to fully understand the dynamics of the network, and the keystone roles played by “undeveloped” lands.

Still, the connections are are clear enough to merit serious attention in the U.N.’s first “Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction,” published last year. Fast-growing slums are singled out as especially vulnerable to natural disasters. Along with improving urban infrastructure, the report underscores the need to protect ecosystems.

SAVED BY A WORM?

According to Fraser and Rimas, civilizations are only as strong as their food empires, and our global food empire is fraying badly. The quick fixes of chemical fertilizers, miracle pesticides, massive water projects and genetically modified seeds have either come up short or led to unintended consequences. Old blights, including Norman Borlaug’s nemesis, wheat rust, are staging comebacks, wiping out crops with as much ruthless efficiency as our increasingly erratic weather.

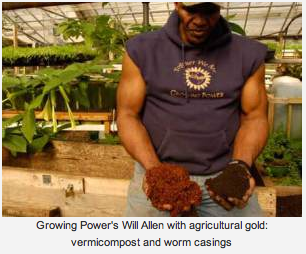

Incorporate a closed-loop aquaponics component, as MacArthur genius Will Allen has done at his three-acre Growing Power farm in Milwaukee, and there is a replenishable source of protein to go with all the fresh veggies. Fish – perch and tilapia by the thousands – swim in water filtered through plants grown in compost fertilized by the castings of red wriggler worms that have munched through mounds of garbage.

The worms - Allen refers to them as “the hardest working livestock on the farm” – are the lynchpin of the operation. They generate the fertility that drives the biomimicked ecosystem, starting with a product that would otherwise end up in a landfill.

Sweet Water Organics, the first commercial scale-up based on Allen’s blueprint, has now been in operation in Milwaukee for about a year. The learning curve has been steep, but the first crops of fish have now been harvested and sold.

Would such an operation work in Pakistan? Possibly. It would not answer the need for grains, which require fields. It would take time and investment. But it could provide a model for a local sustainable food supply. It could be a part of the solution.

So… If you really want to make a make a difference and help save the world, start by planting trees. Lots of flood-slowing, land-stabilizing, biodiversity-nurturing, CO2-absorbing trees. Then be humbled by the talents of worms. Support urban agriculture. Finally, try very, very hard not to repeat the food mistakes of the past. The story, guaranteed, always ends the same grim way.

- “How We Eat, Produce Food, Could Bring Down Society,” interview withEmpires of Food co-author, Evan Fraser / All Things Considered - NPR

- “As Prices Soar, Give Food Some Thought,” op/ed by investment director Tom Stevenson / The Telegraph

- “Beyond City Limits,” by Parag Khanna, Foreign Policy

- “Time to Give: Pakistan Needs the World’s Help” by Jacqueline Novogratz /Huffington Post

- “Maps: How Mankind Remade the World” by Brandon Keim / Wired

- “Scientists call for GM Review after Surge of Pests Around Cotton Farms in China” by Ian Sample, The Guardian

- “Infographic of the Day: How the Global Food Market Starves the Poor” by Cliff Kuang / Fast Company

- “When Tipping Points Collide: On Oil Spills, Dead Zones, Superweeds, Dead Birds, Dead Bees and Not So Funny Laughing Gas,” by J.A. Ginsburg /TrackerNews Editor’s Blog

- “Hot, Cold, Wet, Dry: When Weather Becomes Climate” by J.A. Ginsburg /TrackerNews Editor’s Blog

- “Rebuilding Haiti: On Trees, Charcoal, Compost and Why Low Tech, Low Tech Answers Could Make the Biggest Difference (and How High Tech Can Help)”by J.A. Ginsburg / TrackerNews Editor’s Blog

- “The Farm Next Door: Urban Agriculture, Biomimicry, Aquaponics, Why Worms are Priceless and How Will Allen Aims to Fix the World” by J.A. Ginsburg /TrackerNews Editor’s Blog