wouldn’t be that hard to right.

We didn’t really think too much about it. It wouldn’t have been the first plane to fly into a building there. New York has a history of bizarre accidents: car-swallowing sink holes, water main geysers, gravity-prone construction cranes. Things are constantly crashing and breaking and exploding and toppling in the Big Apple. That’s news?

Besides, we were traveling in a landscape so vast and ancient, so full of mythic drama, everything else fell away. We settled into our insignificance, staring out the window, trying to figure out how one endless vista managed to segue into the next. Yet in the stillness and eternity of that clear blue morning, we were surrounded by evidence of sudden, violent destruction: massive boulders strewn about like so many pebbles, gullies where water had once raged, trees scarred by lightning, twisted by wind.

I called family. I called National Geographic. “Stay put for now.”

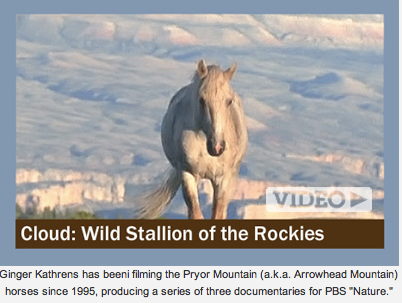

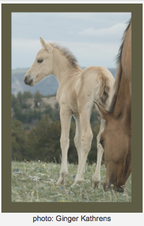

For the next several days, Norris and I shuttled between a Motel 6, where we stayed up nights watching news on old televisions bolted into the cinder block walls of our rooms, and wandering the mountains by day with Ginger Kathrens, a filmmaker working on a documentary for the PBS show “Nature.” She had been following the horses for some time, using the story of young stallion she had first seen as a newborn foal and named “Cloud” as the centerpiece. Ginger, we quickly learned, was the Jane Goodall of wild horses. I am quite sure we wouldn’t have seen what were able to see without her. She knew all the horses’ haunts. She told us of their nuanced emotional lives, and of the dangers they faced from bears, mountain lions, lightning strikes. bitterly cold winters, parched summers and raging wildfires.

She could think like a wild horse. They trusted her. If we were with Ginger, we must be ok.

WAR ON THE RANGE: HORSE ON THE HOOF VERSUS HORSE A LA CARTE

Horses have always been the go-to symbol for the Wild West, embodying all we like to say makes this country special, made it great: strength, courage, independence, maverick (before “mavericky”), free. Yet for years, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which controls vast stretches of public lands, has been circling like a patient predator, shrinking the area where horses can roam by millions of square acres, while painting them as feral invaders whose thirst and sharp hooves destroy grasslands, threatening the prosperity of cattle ranchers. Nevermind that the national cattle herd is almost 100 million strong, while the mustang population has dwindled from 2 million to fewer than 30,000 in the wild. Or that only about 2 million cattle actually use the range, or that grazing leases are often scandalously cheap. The pressure is on as the endgame takes shape:

- Five years ago, the Burns bill, a rider slipped into a massive 3,300 page federal appropriations bill just before the Congress adjourned for Thanksgiving break, made it easier to sell horse meat for consumption abroad.

- A few months ago, the state of Montana passed legislation to encourage horse slaughterhouses to set up shop in the state (although legal challenges are expected to discourage would-be investors).

- In September, the BLM plans to remove 70 horses from the Pryor Mountain herd, which will take it below a genetically viable population. Eight years ago, when Norris and I filmed, the round up goal was to reduce the herd to about 200. Now it’s 120.

| |

Horse a-la-carte may indeed be worth more than horse-on-the-hoof— as a staggeringly gruesome story out of Miami suggests. Seventeen horses in the area have recently been found butchered. No one knows who the killers are, but speculation is rife that an underground horse meat trade commanding prices as high as $40 per pound is behind the crime spree. The legal trade is also bigger than you might think, with ardent gourmands from Canada to France to Japan, where horse sashimi is a delicacy.

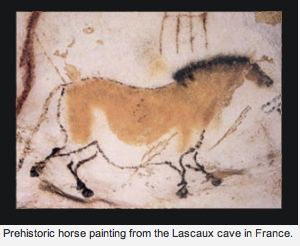

In the five centuries since their ancestors galloped off from the Spanish conquistadors who brought them by ship to the Americas, the Pryor horses have, in their alpine isolation, reverted back to a more primitive form. They have grown smaller overall, with many sporting zebra stripes on their legs and stripes along their backs as well. They are Lascaux horses come to life.

Prehistoric humans, of course, hunted and ate horse, but it was a survival-of-the-fittest battle of wits and cunning. In September, the Pryor horses will be rounded up by a small fleet of helicopters. They will be forced to run for miles over rough terrain, unable to fight or escape the relentless threatening din overhead. Finally, exhausted, they will be led into a coral by a “Judas” horse trained for the task. It will be a scene of hot, sweaty, dusty desperation as the horses are sorted and family bands torn apart. The air will be filled with the frantic cries of stallions separated from their mares.

Some horses will be allowed to return to the range. Some will be auctioned off. Some will end up in “temporary” holding pens where they could spend years in crowded misery. There are now 30,000 horses warehoused in conditions that defy even the loosest definition of humane.

Enter Madeleine Pickens, wife of billionaire T. Boone, who has a plan to adopt – and sterilize – the entire lot. This isn’t the first such attempt to return captured horses to the range, but it is, by far, the most ambitious. Whether it succeeds depends on whether bureaucrats can be coaxed to think beyond their usual boxes.

HOT FLASH(es), PREMARIN, “BYPRODUCT” FOALS & SLAUGHTERHOUSES

If not, it is hard to imagine that these horses won’t eventually end up at a slaughterhouse. Already, an estimated 100,000 horses are butchered each year, mostly at facilities in Mexico and Canada, according to a Humane Society of the United States info sheet.

Horses of virtually all ages and breeds are slaughtered, from draft types to miniatures. Horses commonly slaughtered include unsuccessful race horses, horses who are lame or ill, surplus riding school and camp horses, mares whose foals are not economically valuable, and foals who are “byproducts” of the Pregnant Mare Urine (PMU) industry, which produces the estrogen-replacement drug Premarin®. Ponies, mules, and donkeys are slaughtered as well.

Surely, there must be a better biotech answer for hot flashes.

A couple of years ago, not far from where I live just north of Chicago, a semi packed with 59 horses overturned on a highway at night. The driver told police he was making a delivery from an auction in Indiana to a breeder in Minnesota, though many suspected the horses were ultimately destined for slaughter. Nineteen horses died from the accident. Another required extensive surgery. The owner was eventually fined $4,000 and senteced to supervision.

If indeed we are what we eat, bon appetit…

ANCIENT HORSES & A RETURN OF THE NATIVE

Watching the horses in the Pryors on that saddest of September days felt like looking back in time to a better time. Horses – equines - evolved in North America over tens of millions of years. There were dozens of species of every size and shape, adapted to all kinds of niches, surviving countless shifts in climate. But between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago they disappeared, wiped out along with an ark full of megafauna that included mammoths and camels (yes, camels).

Nevertheless, the equine family survived. Over their long history, some had trotted into Asia via the Bering land bridge, and from there branched into new species settling in Siberia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. It wasn’t until Columbus headed West in search of the Far East just over 500 years ago that horses once again were seen in their old home, the New World.

So are they feral invaders? Or is the story of the American horse more a “return of the native”?

It seems hard to believe that stone age hunters, even those armed with the sharpest of Clovis points, could have taken out a species so exquisitely refined by evolution to outrun a raft of tooth & claw predators and tough enough to survive in the most edgy of environments. The only way Norris and I managed to find the Pryor horses was with an SUV, a rough semblance of a road and an experienced guide. They were tucked away in mountain passes where only helicopters could ferret them out.

But perhaps the Pleistocene herds were weakened in some way. Maybe they faced a “perfect storm”: increased hunting pressure, the emergence of new diseases affecting both fertility and mortality, and the floods, fires and famines that came with an ice age giving way to a warmer planet.

HOME, HEARTBREAK & HOPE

Norris and I eventually drove home, absconding with our rented SUV for the cross-country journey while the airlines struggled to resume service. We knew, though, that as soon we left the Pryors, we would lose the protection of our unexpected Shangri-La. The grim reality of our world and time would be inescapable. As we headed east across the Minnesota border, NPR’s signal was finally strong enough to give the Rush Limbaugh station some competition. Miles flew by. Our hearts grew heavier.

The World Trade Center was just a smoking hole by the time I got to New York. Flyers with the faces of the missing were stapled to wooden walkways across the street from Ground Zero. I joined a silent procession walking past dazed and aching.

I often cover stories where hope is in short supply: Ice sheets melt. People starve. Women are raped. Pandemics threaten. Drugs are faked. Water is polluted. Fields are parched. People enslaved. Forests disappear. With so much so wrong, how can things possibly turn out well? Where do we even begin to make a dent? The reflex is to prioritize for triage, to figure out whether to go after open wounds or underlying causes. But it is all urgent.

So where do a few dozen, or a few hundred, or even a few thousand wild horses fit into the scheme of things? This is one of those rare instances when doing nothing (the Pryor round up), or doing something fairly easy (hashing out the Pickens’ proposal), or simply putting a stop to something (Premarin) could make a significant difference.

Doing right by horses is simply the right thing to do.

There is also a powerful symbolism. As the years go by, the rituals of 9/11 remembrance have begun to feel staged. We remember the date, not the day. The Twin Towers have faded into abstraction.

But the wild horses still endure in triumphant defiance. They are a legacy from our nation’s past and from an even deeper past. Their existence provides a gift of perspective, without which it will be that much harder to find our way.

Despite protests that included tens of thousands of emails, calls and faxes to BLM administrators, the pleas and prayers of a Crow elder, a last minute legal challenge and swell of too-late national news coverage, the round up of the Pryor Mountain wild horses went forward as planned last week.

It was everything feared and then some – as chronicled by filmmaker Ginger Kathrens’ daily blog posts. Observers weren’t always allowed to observe. The BLM waffled on its decision that captured horses would be available only for adoption (requires some vetting), opting to put some up for straight sale (no vetting). Since older horses are harder to train and thus less adoptable, they could languish in government holding pens for years or, potentially, end up in a slaughterhouse.

The youngest horses – even those returned to the wild – also face an uncertain future. Kathrens filmed a foal so lame, she could barely walk after being helicopter-herded for miles down rugged terrain, galloping from an alpine paradise at 8,000 feet to a dusty desert corral at 3,000 feet.

Beyond the disturbing question of why our government is spending any time or money on such folly lies a question perhaps even more disturbing: Why there are so many foals on the mountain this late in the year? Foals are supposed to be born in spring so they can fatten up on summer’s sweet grasses to grow strong enough to survive Montana’s long harsh winters. Horses born too late in the sesason are at a severe disadvantage – as are their nursing mothers. Weakened by cold and dwindling forage, they are more vulnerable to disease and make easy marks for predators.

So what’s going on? What’s mucking with the equine reproductive clock? Something called Porcine Zona Pellucida or PZP, an “immunocontroceptive” designed to keep mares from conceiving. The vaccine triggers an immune response that alters the shape of sperm receptors on the surface of egg cells so sperm can’t get in.

Only, apparently, a few do…

Stallions will simply keep trying to get mares pregnant, even outside the normal mating season. Eventually, as the vaccine’s effects begin to wear off, they succeed.

Ironically, the young foal wobbling around in agony was a member of a band brought in to give mares shots of PZP.

- “Cloud: Challenge of the Stallions,” Ginger Kathrens’ third documentary for Nature(PBS) premiers on October 25, 2009 (preview)

- “Cloud’s Legacy: The Stallion Returns” by Ginger Kathrens (book)

- The Cloud Foundation: a not-profit started by Ginger Kathrens that focuses on wild horse issues

- “Saving the American Wild Horse”: companion website for documentary by James Kleinert, featuring Viggo Mortensen & Sheryl Crow among other horse historians and experts; narrated by Peter Coyote:

| |

- The American Wild Horse Preservation Campaign

- The Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary: author Dayton O. Hyde’s horse refuge in South Dakota

- Help Save America’s Wild Horses: Madeleine Perkins’ website