|

All photographs on this website, unless otherwise noted, are copyright 1995, The Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona Foundation. For information on licensing, please contact CCP. For information about signed silver prints, please contact J.A. Ginsburg.

|

|

(On Martin & Lewis)

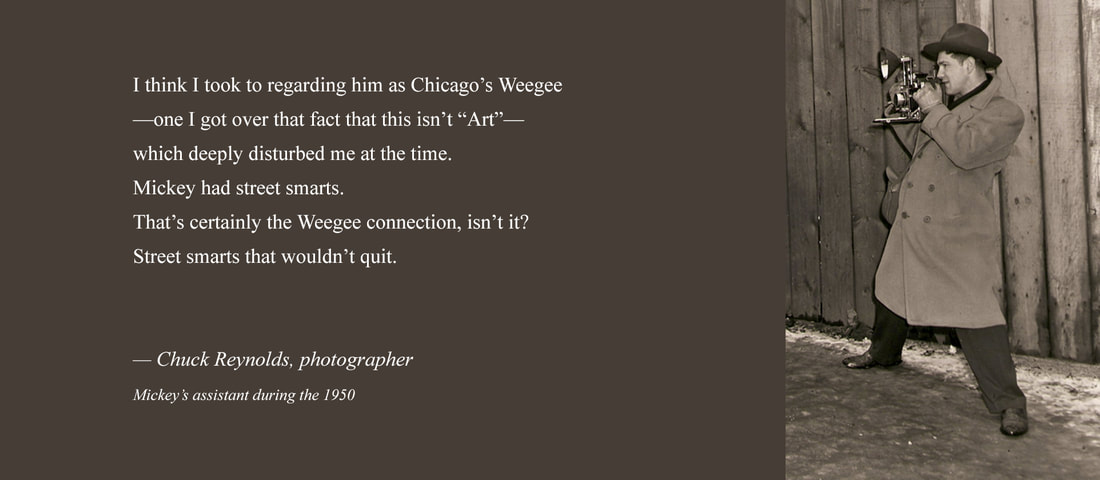

"The crowds adored them. Then, one night after the show at the Chicago Theater, a woman put her hands around Jerry's neck and started to choke him and would not let go. That night, he said, he learned to scan the eyes of the crowd, looking for the "'loony birds.'" — Roger Ebert, film critic, Chicago Sun-Times (Address to Southern Baptist Leaders)

“While the so-called religious issue is necessarily and properly the chief topic here tonight, I want to emphasize from the outset that I believe that we have far more critical issues in the 1960 election: the spread of Communist influence, until it now festers only ninety miles off the coast of Florida—the humiliating treatment of our President and Vice President by those who no longer respect our power—the hungry children I saw in West Virginia, the old people who cannot pay their doctor's bills, the families forced to give up their farms—an America with too many slums, with too few schools, and too late to the moon and outer space.These are the real issues which should decide this campaign. And they are not religious issues—for war and hunger and ignorance and despair know no religious barrier..." —John F. Kennedy, 1960 “You won’t have Nixon to kick around any more” -—Richard M. Nixon in a press conference after losing the California governor’s race, 1962 "The fifties and early sixties were so great. And we lost it. I don’t know how we lost it, but we did."

—Dick Biondi, disc jockey “Standard Oil was a good company. We all raised our families and bought our homes working for Standard Oil. And we had good benefits. And today we’re retired with good benefits. We had a savings plan that was one of the first in the region. How could we fault this company? We had nothing but good to say. That’s what our club is built on...

...When we came home (from WWII), none of us had automobiles. When we were young, we walked everywhere we went. You walked, or there was bus transportation or streetcar. Then all of a sudden everybody wanted an automobile. And everybody got an automobile.” —Jim Thorpe, retired machinist, Standard Oil "Wouldn't you really rather have a Buick?" —ad campaign "We all came out of the service. 90% of us were single. What was the first thing you look for? You look for a wife. They were home waiting for you. You were starting to get up in your 30's, so the family was the thing. You started to have a family right away. And everybody was looking to buy a home. So the job and the family and the home: this is what we built out lives on."

—Jim Thorp, retired refinery worker "They couldn't possibly get away with that kind of use of women today. It was acceptable then in a way that no one even questioned."

—Joel Snyder, professor, University of Chicago |

by Kenneth C. Burkhart, co-curator

The time period represented in the exhibition, Mickey Pallas: Photographs 1945 —1960, signifies a turning point in American history. Rallying from the effects of the Second World War and facing and unprecedented economic growth over the upcoming twenty years, the nation began to set aside notions of strength and security established in its past, and instead began to look to its future for promise and hope. Mickey Pallas managed to record this neglected era, producing a remarkable document about the fabric of American life.

The post-war years, as described in Nicholas Lemann’s book, Out of the Forties, stand out as, “a watershed, the end of a long bad time and beginning of a time of great confidence, prosperity, and change.” Americans recovered from a devastating war, which was preceded by one of the worst depressions in history, and was concluded shockingly by the first atomic explosion. As they began to abandon the ration stamp mentality, war technology was applied to domestic needs, bebop took hold, and the first wave of baby boomers was being strolled down Mainstreet, U.S.A. The economy took on upward turn. Life was hardly a bowl of cherries. By 1950 Senator Joseph McCarthy began his scathing accusations of communist infiltration in the State Department, an accusation that was to spill over into other government agencies and American institutions. McCarthyism darkly reflected the paranoia that had developed during the war years, manifesting itself at a time when so much appeared to be at stake in this new growth period. In 1951, North Korea broke through the 38th Parallel into South Korea, once again signaling to Americans that their ideals were in need of protection. Despite this evidence of turmoil at home and overseas, Americans retained the desire to move forward as a people and to pursue the fruits of peace and prosperity. Still, for the majority of Americans, it was a decade of opportunity. As John Chancellor so aptly stated in the The Fifties, “If you weren’t looking for work, black, or getting shot at in Korea, it was a very nice time,” In 1948, there were already a million television sets serving a population of 150 million; by 1951 the number had climbed to 15 million; and by 1960 there were 85 million. Making up only one-sixth of the world’s population in 1954, American’s owned 60% of all cars, 58% of all telephones, and 45% of all radios. At a time when the prospect of nuclear holocaust necessitated regular air raid drills in grade schools, and the distribution of Civil Defense brochures on building home bomb shelters, America used its newfound leisure time and income to sedate itself through entertainment. Those lucky enough to reap the rewards of the new economy watched TV, went to movies, and saw the “U.S.A. in their Chevrolet.” For them, the fifities were tranquil and fabulous. The common laborer was experiencing a very different kind of growth. In his book, Out of the Jungle, labor historian Less Orear described the strength of the union then as existing “in its capacity to turn personal frustrations beyond the individual to a larger commitment to the collective good.” Unionization of labor, which had gained momentum during the depression, suffered a sharp decline with the onslaught of war. By the late 1940s the labor was once again negotiating for such concessions as geographic wage consistency, and binding arbitration of grievances. This was to set the stage for several major strikes within the meat and sugar industries during the 1950s and 1960s. These disputes affected a work force that was made up of all races and nationalities, men and women, who had not only worked side by side to put bread on the table, but who marched side by side to fighting for their collective rights as workers. At the working class level, the differences between the races and culture groups were insignificant when compared to the common cause of gaining a larger piece of the pie. For Black society as a whole, however, advancement remained elusive. The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) reported that 1946 was “one of the grimmest years” in the history of that organization. Returning Black veterans were subjected to the same discrimination, and in some cases outright brutality, as had existed before they mobilized to defend their country. In spite of the slow start, the next 15 years would indeed introduce many “firsts” for Black Americans as well. The first issues of Ebony and Jet magazines hit the newsstands with lasting success. Jackie Robinson became the first Black to be signed by a major league baseball club. Following the Truman administration’s appointment of the first Presidential Committee on the Civil Rights, America received its first Black delegate to the United Nations., General in the U.S. Air Force, and member of the U.S. Supreme Court. The first Black recipients of the Nobel and Pulitzer prizes were announced. And in a bittersweet twist, 1952 proved to be a notable year statistically: It was the first year in 71 years of record-keeping that a Black was not lynched on American soil. Photography, also at a cross-roads at this time, played a major role in bringing to light the anxiety and aspirations of this era. The deeply rooted ideals of documentary photography had been given wide exposure through the government’s FSA (Farm Security Administration) program in the 1930s, infiltrating nearly all levels of photographic illustration. Roy Stryker, an unwavering champion of the documentary spirit, saw photography as the ideal means for giving substance to the American experience. It was the ultimate form of propaganda, providing at the same time a unique record that could never be repeated. The post-war years also represented the zenith of the photographic essay. Major publications, including Life, Look, The Saturday Evening Post, Ebony, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vanity Fair, were in their heyday, relying heavily on the talents of such photographers as W. Eugene Smith, Lisette Model, Arnold Neuman, Louis Dahl-Wolfe, and Elliot Erwitt. Photographic editors established the aesthetic of these flourishing publications. At the other end of the photographic spectrum was a new movement of photographers known as Group f/64. Spurred on by Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and others, it put to rest the last inklings of pictorialism, which had dominated the amateur and art photography community well into the 1930s. In fact, after the war years, photography as art made inroads on many fronts. In 1949, the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House joined the ranks of the few major museums with photographic collections by establishing its own key collection and exhibition schedule. In 1952, Minor White and other introduced Aperture, a landmark publication and outlet for the creative photographer. That same year, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment was published, taking the genre of street-shooting and photojournalism to their highest levels. The Gernsheims published their seminal work, The History of Photography, in 1955. At the same time, Edward Steichen, then director of the photography department of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, organized and mounted The Family of Man, which was heralded by many as the exhibition of the century. Steichen attempted to show how the universality of life transcends cultural boundaries. He later described photography as “the best medium for explaining man to himself and to his fellow man.” Perhaps the single most important publication in the 1950s was Robert Frank’s The Americans. This milestone photographic essay illustrated Steichen’s “explanation” theory all too well, showing not a country in a fabulous or tranquilized state, but a nation characterized by suspicion and bias within a strangely surreal landscape of fifties attitudes. Jack Kerouac, one of Frank’s contemporaries, applied a Beat description to the book and its creator: “Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world” In one stroke, Robert Frank had summed up one era and laid the foundation for the next. For Mickey Pallas, these were times both for photography and action. Following assorted jobs in the mid-1940s, Pallas was quick to embrace photography as a career and a life’s endeavor. Raising during the depression years, Pallas pursued his craft with his own Keruoacian energy, choosing clients that held the excitement and adventure he did not experience as a child. In Chicago, some of his first assignments were for labor unions. Their challenge to Big Management became, for Pallas, an opportunity to make a living and to become involved with the movement. An empathetic activist at heart, he recorded union meetings, rallies, and strikes; visually synthesizing the events and participating at the same time.

Pallas broke new ground as a white Jewish photographer by shooting a predominantly Black audience: the Reverand Cobbs’ First Church of Deliverance in Chicago. He also shot for Ebony magazine, and traveled with the Harlem Globetrotters. His recognition of the universality of humankind is evident in these images and it remained a distinct part of his work throughout his career. As a chronicler of the earliest days of television, Pallas applied his sensitive eye to unveiling the often comical beginnings of this super-industry from the inside. Pallas’s work revealed him to be as comfortable rubbing elbows behind the scenes with the stars of yesteryear as he was at ease shooting the last year’s of burlesque, on of the first victims of the new electronic form of entertainment. As Pallas’s feeling for his fellow human beings developed, so too did his personal vision. His photography became an extension of his sensibility. Pallas approached his subject in a straightforward, uncluttered manner. His forte was the ability to encapsulate a person or an event in a single image, or produce a picture story through a series of images linked to a single theme. He was masterful at perceiving and preserving the reality that surrounded him. Perhaps the most telling group of images within Pallas’s complete body of work are his portraits of the common worker. Whether shooting on location or in a studio, Pallas captured the substance of America and the elusive American Dream. In the same way August Sander’s extensive portraits said more about class structures than merely the occupational dress of the pre-World War II German people, Pallas’s images run deeper than the veneer of workaday life in the forties and fifties: the faces in Mickey Pallas’s portraits transmit both the hope and the pride that defined post-war America. (Next page: biography / contact) |